1. Introduction

In the past decade, we have seen some interesting changes in regard to network connectivity, especially on the private connectivity between datacenters. We are now at a point where you can get 1-10-100 Gbps private circuits with guaranteed bandwidth and minimal packet loss between different geographical locations. However, we are also seeing a strange behavior where, in some specific cases, we cannot use that bandwidth at full capacity. In this blog entry, we will discuss how link latency impacts throughput and discuss some ways of improving the throughput on high-latency networks.

A small recap on TCP

The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is one of the main protocols of the Internet protocol suite and most of the applications we use today rely on it to move data across the networks. We will not go into details because TCP is a very complex protocol that uses various mechanisms to ensure reliable data delivery and explaining all of those is not the purpose of this blog. We will, however, focus on one parameter called “TCP window” and why it matters in certain scenarios.

In Layman’s terms, the TCP Window parameter tells how much data can be sent by an endpoint before it stops and waits for the receiver to send an acknowledgment packet. The parameter is a 16-bit field in the TCP header, therefore it has a max value of 65536 bytes. While networks improved, it quickly became obvious that a maximum of 65536 bytes is not enough to fill large bandwidths so a new RFC – 1323 – was developed which improved TCP by introducing a new concept called “TCP window scaling” which provides a new mechanism of announcing the TCP supported window by announcing the supported scaling factor. Without going into further details, with this new mechanism we can use the 16-bit field to announce a 30-bit max TCP window which can now reach 1GByte.

How TCP impacts throughput on high-latency networks

To understand how TCP is related to the network throughput we need to discuss a concept called bandwidth-delay product which is the product of a data link’s capacity (in bits per second) and its round-trip delay time (in seconds). The result, an amount of data measured in bits (or bytes), is equivalent to the maximum amount of data that has been transmitted but not yet acknowledged. The definition resembles the one for the TCP Window and it is true, BDP tells us how big the TCP window should be for a single TCP stream to fill the available bandwidth while considering the link’s delay.

Let’s take a practical example of a 1 Gbps link and a 50 ms latency. For those values, BDP would be:

1000000000 (link capacity in bps) x 50 / 1000 (latency in seconds) = 50 megabits or roughly 6 MBytes

If we want one single-stream of TCP to fill the entire available bandwidth we will need to configure a TCP window of 6MB because the TCP Window must be equal or greater than the BDP. But can we configure it? The answer is “not really”. The TCP window is not a configurable parameter, however the Operating Systems provide the means to “encourage” TCP to use a specific Window and that set of parameters is called TCP Buffers.

The TCP Buffer is a kernel variable that tells the OS how much RAM it can allocate to each TCP session. TCP will then use its internal mechanisms to scale the TCP Window to fill that buffer. We will look at how to configure TCP buffers on Linux systems in the demo part of the blog.

The general best practice is to test and see how much throughput a single TCP stream has on the link and then use parallel file transfer to fill the available link bandwidth. However, that is not always possible, or the TCP window is so small that it would require tens of parallel streams to move any meaningful amount of data.

A discussion on tools

While we are tuning TCP it is very important to understand that TCP is just a protocol used by applications and that those applications matter a lot when discussing throughput. Let’s review some of the well-known applications which we will use in our demo:

- SCP and RSYNC (default mode) – these applications have been the “go-to” for data transfer for a long time. They are secure and easy to work with from the cli and perfect for automation. The main issue with both of them is that they rely on SSH and SSH was never designed for high throughput data transfers, especially over high-latency links. We will see in the demo part that SSH throughput grows with the TCP Window up until a point where it caps as the SSH protocol is limited to a 2MB maximum TCP window. An improved SSH protocol called High-Performance SSH (HPN-SSH) is being developed which will take out all restrictions related to TCP windows, but it is not yet mainstream.

- RSYNC – DAEMON mode – Rsync can be used in daemon mode so it will use its internal mechanisms for data transfer as opposed to using SSH. In this mode, the traffic is not encrypted and the session runs on port 873 instead of 22.

- CURL – Curl seems to make use of the whole TCP window, therefore it was a good tool to see the actual progress after TCP Buffer modifications, but it has the small downside that it needs an HTTP server on the other endpoint and further configuration if we want the traffic to be encrypted. In my tests, I used only HTTP (no encryption) because HTTPS performance is not our focus. Of course, Curl can be used with other protocols such as FTP instead of HTTP, however we will only focus on HTTP to prove that TCP window does make a difference.

- IPERF – iperf is the most used tool to measure network throughput and we will use it as a baseline for the tests.

2. Tests

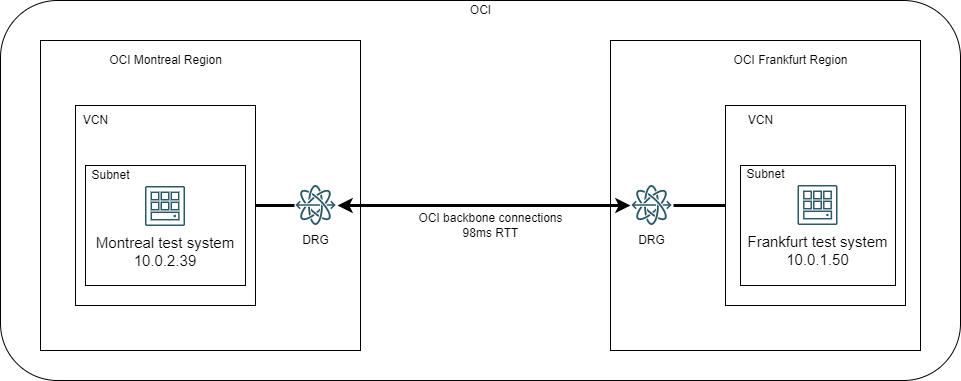

In part two we will look into a real-world scenario where we modify TCP Buffers to increase the network throughput. First, let’s take a look at the lab diagram:

Test Setup

-

We will use 2 Compute instances in different OCI Regions and interconnected over the OCI backbone. The latency between the two regions is roughly 98ms, a value we will use in our calculations.

-

Both Compute Instances run Oracle Linux 8.5 and have sufficient resources (CPU, RAM) to be able to handle high network throughput (>1Gbps).

-

We will consider the available bandwidth between the Regions as 1Gbps even though the OCI backbone supports much more than that.

-

We will do one batch of tests with OS default values for TCP buffers, 1 batch of tests with increased buffers values targeting half of the available bandwidth – 500 Mbps, and 1 batch of tests targeting the “maximum” throughput of 1Gbps per single-stream

-

Each batch consists of:

-

1x IPERF3 Test, single-stream

-

1x IPERF3 Test, multi-stream to fill the bandwidth

-

1x 2GB file transfer with SCP, default application values

-

1x 2GB file transfer with RSYNC, default application values

-

1x 2GB file transfer with RSYNC-DAEMON, default application values

-

1x 2GB file transfer with CURL, default application values

-

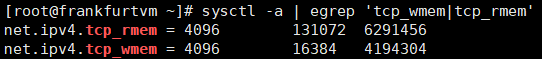

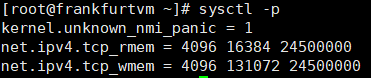

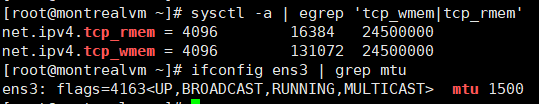

The Linux Kernel provides two parameters to increase the TCP buffers: RMEM (read TCP buffers) and WMEM (write TCP buffers) and they are configurable through the system tool SYSCTL.

To view the default values, we need to use “sysctl –a”:

The system presents 3 values for each of the buffers. Those 3 values (measured in bytes) have the following meaning, from left to right:

- The first value (4096) is the minimum TCP buffer that can be allocated to a session

- The second value (131072 for RMEM and 16384 for WMEM) is the default buffer allocated

- The third value is the maximum TCP buffer that the OS can allocate, and it is the one we are interested in because it is directly correlated to the max TCP Window the OS can support

One important thing to consider is that the Linux OS will allocate half of the value to internal processes and a half to the actual buffer which will allow the TCP window to grow. So, the max TCP Window on the default kernel settings is 3Mbytes (half of the RMEM max value).

For a more complete list of OS specific TCP parameters on different Operating Systems please visit: tcpip-tuning

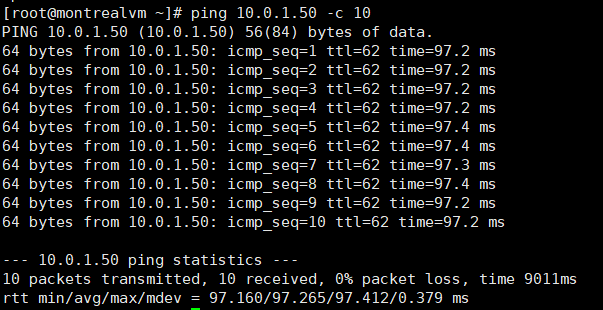

Before we start let’s observe the link RTT:

We will round those values to 98ms.

Default values tests

By knowing the maximum TCP window the OS supports (which will be the BDP) and the TTL of the link we can calculate the maximum throughput a single TCP stream can have.

Max Throughput = BDP (TCP Window) / RTT so, in our case it’s

3 Mbyte / 98 ms = 24 Mbits / 0.098 s = 250 Mbps

One thing to point out is that all these values are roughly calculated as we are not really interested in precision.

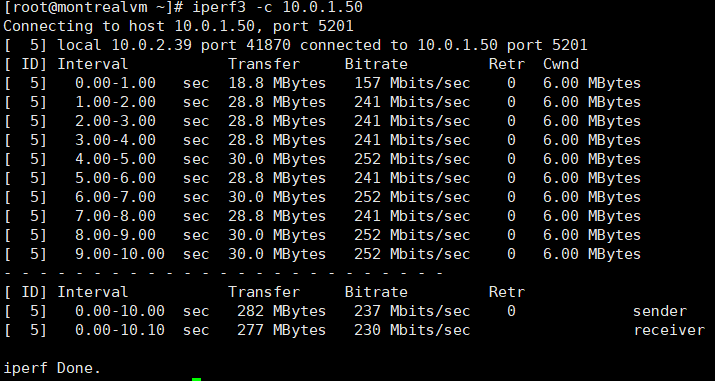

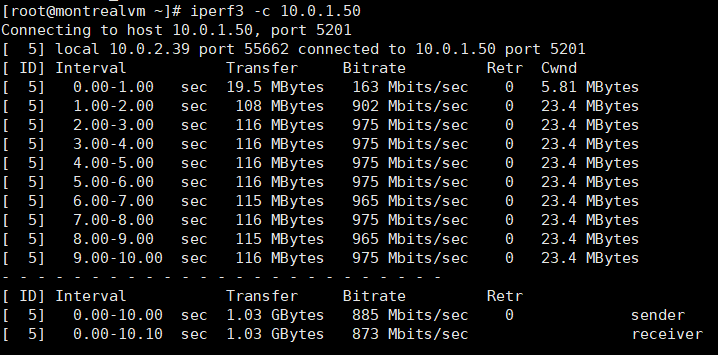

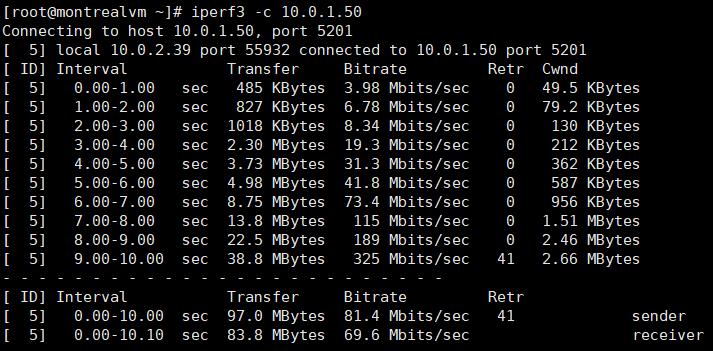

Iperf3 single-stream:

As we can see, iperf can use most of the available bandwidth for a single-stream. To fill the entire link we will use 4 parallel streams (iperf3 -c 10.0.1.50 -P 4).

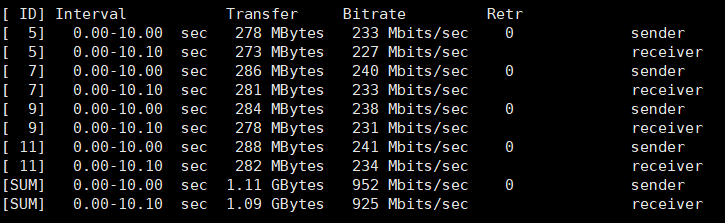

Iperf3 parallel streams:

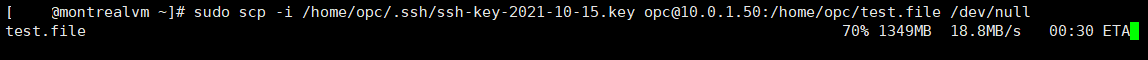

SCP:

![]()

SCP had max speed of 18.8 MB/s (roughly 150 Mbps) and an average speed of 14.9 MB/s

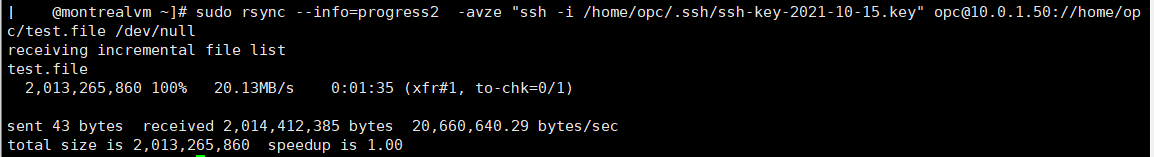

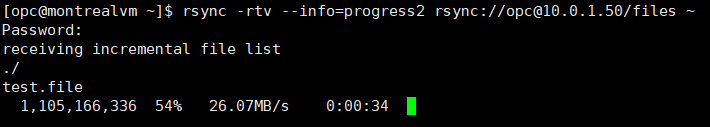

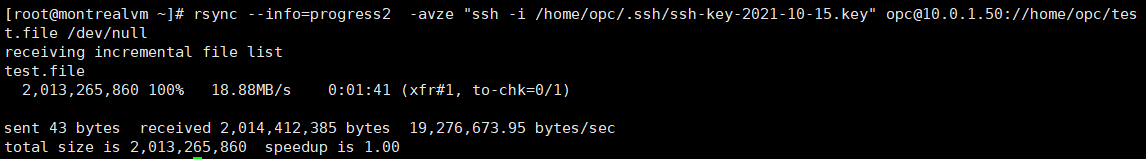

RSYNC:

Rsync had a top speed of 20.46 MB/s (164 Mbps) and an average speed of 20.13 MB/s.

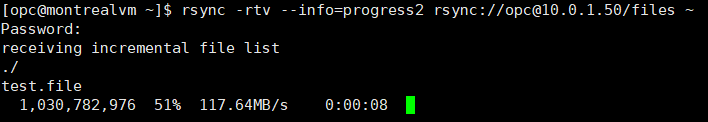

RSYNC-DAEMON:

RSYNC in daemon mode is reaching 210 Mbps.

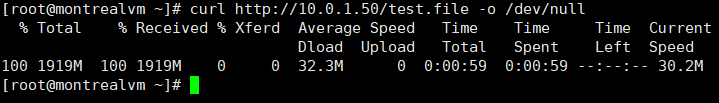

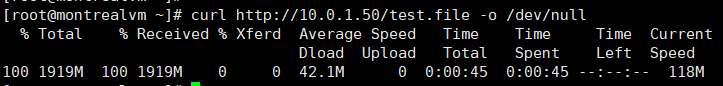

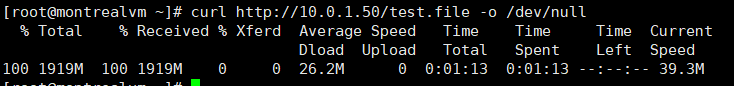

CURL:

Curl was able to reach 32.3 MB/s (258 Mbps) and fill the available bandwidth.

Tuned values – target 500 Mbps

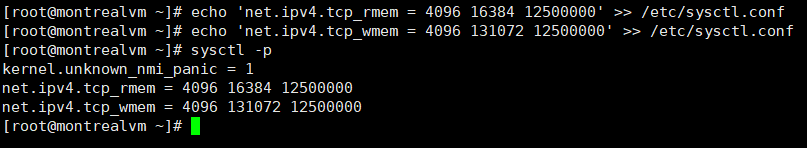

According to the BDP formula, to reach 500 Mbps per TCP stream (for a 98ms TTL value) we need a TCP window of 6.125 MB so we will have to put the double of that (12250000 bytes) as a TCP buffer.

To modify the default values we need to put the new ones in “/etc/sysctl.conf” and input “sysctl –p” so the kernel loads the new parameters. We need to do this on both endpoints. I will put 12500000 to account for the rough calculations.

The test results are:

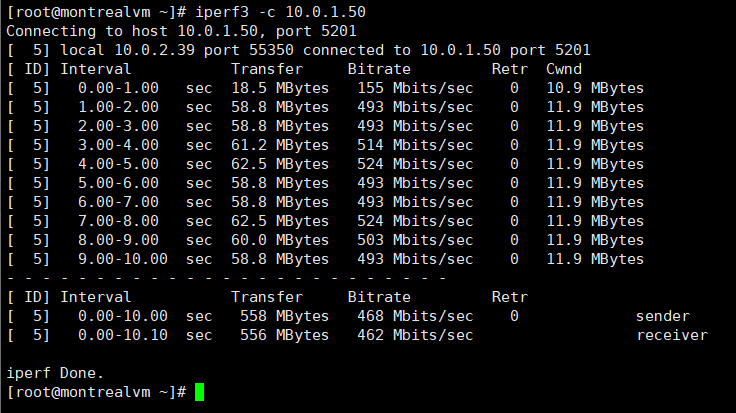

Iperf3 single-stream:

Iperf3 multi-stream (2 streams):

SCP:

![]()

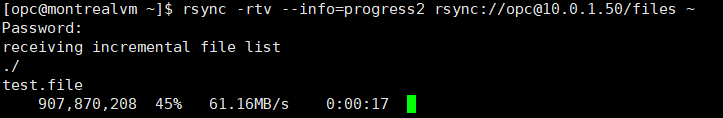

RSYNC-SSH:

RSYNC-DAEMON:

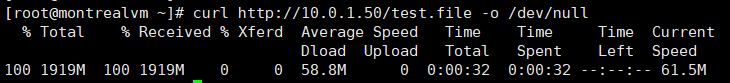

Curl:

Preliminary analysis: IPERF,Curl and RSYNC-DAEMON were able to reach the 500 Mbps target while SCP and RSYNC-SSH have no obvious improvement.

Tuned values – target 1 Gbps

According to the BDP formula we should have a TCP window (or BDP) of 12250000 bytes. So we will again increase the TCP max buffers to 24500000 bytes or 24.5 MB. Remember to this on both ends. Here is how it should look in the end:

The results are:

Iperf3:

SCP:

![]()

RSYNC-SSH:

RSYNC-DAEMON:

Curl:

Preliminary analysis: IPERF,Curl and RSYNC-DAEMON were able to reach the 1 Gbps target while SCP and RSYNC-SSH have no obvious improvement.

A discussion on MTU

MTU has a huge impact on performance. All the tests we did so far were on MTU 9000 on the endpoints and on the network between the endpoints. All these theories and formulas are no longer relevant if the endpoints will have to split the packets into small chunks to accommodate a 1460 MSS/1500 MTU. And to see the impact, let’s see what IPERF and CURL look like on a 1500 MTU network. The TCP window is 24500000 so we have a theoretical speed of 1Gbps per stream.

IPERF3:

Iperf3 was able to reach 300 Mbps but averaged at about 80 Mbps. The same Iperf on a 9000 MTU network was able to reach 900 Mbps per stream.

Curl:

Curl was able to reach 300 Mbps too, briefly, but the Average was about 200 Mbps. The same Curl, with MTU 9000, managed to reach 950 Mbps for a single TCP session.

As a rule, for 1 Gbps links and above, the network should use Jumbo frames (9000 MTU) to be able to do single-stream high throughput.

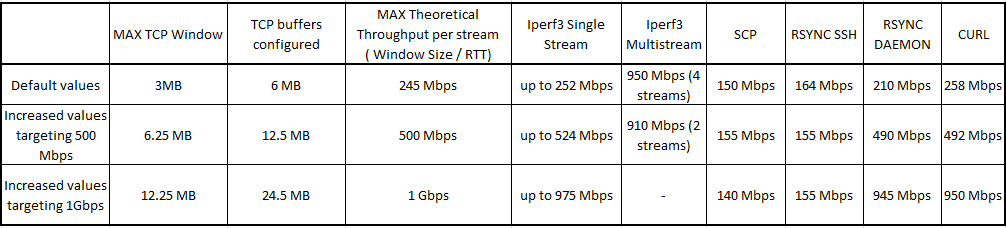

Test results

I’ve gathered all the results in a table so we can see the impact of modifying TCP buffers. All the values below are for MTU – 9000 bytes:

By looking at the table we can draw the following conclusions:

- TCP Buffers do impact the TCP window selection mechanism as we were able to reach 950 Mbps for a single file transfer over a high-latency network

- Applications like Iperf3, Curl and RSYNC (running in daemon mode) can take full advantage of the increased buffers and will scale to fill all the available bandwidth

- Application like SCP and Rsync (SSH mode) are dependent on the underlying protocol (SSH) and they are heavily limited by SSH’s max TCP window value of 2MB as we can see they never go past 160 Mbps (160 Mbps is the max throughput on a 98ms link with a 2MB TCP Window).

3. Final words and conclusion

As private connections to the cloud, like OCI’s FastConnect, are the optimal way to connect private datacenters to Cloud workloads, we must understand that we still rely on protocols such as TCP to move data around. More than that, we are now at a point where the WAN has huge throughput (10-100Gbps) but also high-latency because of physical distances and that latency has a big impact on how fast we move data.